Synopsis

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

Introduction

During my years as a university student studying business administration, I developed and presented independently the ideas that became the strategic foundation behind the government‘s decision of forming the Vatnajokull National Park, which is Western-Europe‘s largest national park. I was the only one in history to ever present ideas and arguments for that, as the Vatnajokull glacier and other glaciers in Iceland were a type of area that conventional nature conservationists were never interested in. The fact that I was the mastermind behind such a huge decision of the government, while being a university student working alone and uncompensated, is probably nearly unique in Europe‘s history in the 20th century. It is very uncommon that undergraduate students influence national governments so directly in such a large decision. The historical data is available, which proves my part in this and outlines the limited activity of others in discussing or presenting their own propositions, in the years before the issue was taken up by the parliament. This data is all in Icelandic, among other in a book named Skrefin ad Vatnajokulsthjodgardi. However, I only presented the very novel ideas for others to speculate about. I wasn‘t campaigning for this, and didn‘t put much work into talking to people and establishing contacts. Thus I wasn‘t connected in the political process. I actually didn‘t know about the decision that was being made, and many didn‘t know about my fundamental role either, as my name wasn‘t being held up high. I was an unknown and unconnected university student . At the same time, there were fierce disputes starting over a proposed hydropower and heavy industry project in the same and nearby area, between nature conservationists and those who supported the project. The project would be the largest in Iceland‘s history, worth US$ 3 Billion combined. This probably meant that there were some who didn‘t like, or were suspicious of, the proposed national park at the same time as they were campaigning for the large hydropower projects, in a struggle with nature conservationists who were trying to stop the large projects. Instead of enjoying some benefits for my contribution, I encountered some very serious challenges in building up a career. These challenges have continued for far too long, and need to be understood for me to be able to continue with other, promising opportunities. That is why this story is explained here.

Sverrir Sv. Sigurdarson of Reykjavik, Iceland

Table of Contents

Part Two – Past Accomplishments. 24

The Vatnajokull National Park. 24

The true origins of the first, basic propositions. 26

The scope of public discussion: It didn‘t exist. 27

My strategies presented and received positive reactions. 27

Parliament and ministers made their decision. 30

Harsh disputes were rising with bad consequences. 30

I had been the only one with a valuable idea. 32

Misunderstanding regarding the true origins. 33

The full story was not easily visible. 34

Explaining this is probably necessary. 37

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

The Vatnajokull National Park

The Vatnajokull National Park is Western-Europe‘s largest national park. It covers around 14,000 square kilometers, or around 14% of the total area of Iceland. Within its boundaries are some of the country‘s most remarkable natural landmarks, and the geological diversity is very great. Within the park, you find Vatnajokull which is Europe‘s largest glacier, Oræfajokull which is Iceland‘s highest peak, Dettifoss which is Europe‘s most powerful waterfall, and a number of other waterfalls, active volcanic areas both under the ice cap and outside, some of which have erupted in recent years, and mountains, rivers, sands, lavafields, highland meadows, springs, geothermal areas, and more. It includes the famous Jokulsarlon glacier lagoon, which was featured in two James Bond movies. The national park has the potential as a natural wonder of becoming well-known among the public in the western world, and could become very valuable econmically, as a magnet for foreign tourists, according to official estimates.

Images from the Vatnajokull National Park, various photographers.

The national park is also situated close to the reservoir of the Kárahnjúkar hydropower station. The decision of forming the park was taken around the same years of the decision to build the hydropower station and the accompanying aluminum smelter, and that is not a coincidence.

The true origins of the first, basic propositions

So the question is, how did it happen that politicians at the time one day had in front of them a proposition for forming this type of a park, in this location? Why were they interested in the decision of forming it? What kind of arguments had been presented for them? The political majority at the time was center-right wing, with the ministers in the government coming from those parties. The right wing party had historically been very uninterested in nature conservation, and instead, being very pro-hydopower and heavy industry. The fact that this political party turned out to be interested in forming a huge national park in the vicinity of the hydropower project was very unusual, so the arguments must have been unusual too.

If historical data is analyzed, then it becomes clear that the decision of politicians in the beginning to form the national park must have been influenced by two thoroughly argumented theories, or strategies. Number one was the theory that the image of Iceland for it‘s unspoiled nature could be strengthened, by creating a very large protected area or national park, and tourism and even others sectors of the economy could benefit from that. This was a proposition for creating jobs.

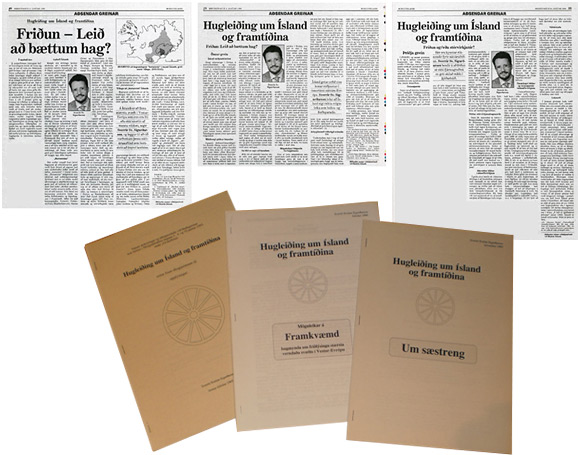

The three first newspaper articles from January of 1995, and three additional papers distributed in 1995 to all members of parliament, ministers and other influential individuals.

Number two was the unusual theory, that if Icelanders decided to go ahead with large hydropower- and heavy industry projects, then it could be beneficial to create a very large nature protection area at the same time, to show a positive attitude towards nature. The hydropower and industrial sector could even benefit from that, in the big picture. This was thus a proposition for consensus.

These two strategies were of an entirely new kind, compared to ordinary nature conservation ideas. The proposition was that this kind of park could be formed on and around the Vantajokull glacier. Conventional nature conservationists had never been interested in protecting the glaciers of Iceland, and they would never present an idea that hydropower projects could benefit from a large park that would be formed alongside such projects. They were generally very opposed to any new energy projects, and wanted to protect the nature rather than to see such projects becoming a reality. Nature conservationists had presented many wishes regarding areas to be protected. These areas were on the so-called Nature Conservation List (Náttúruminjaskrá) which is a kind of a waiting list with areas that have not been formally protected. There were somewhere around 260 areas on the list, but Vatnajokull and the other large glaciers were not on the list. This simply shows how nature conservationists were not interested in the glaciers.

Strategy number one was based on the increasing interest in environmental matters and the protection of nature among the public, in the two decades before this. This had created an increased demand for experiencing unspoiled nature, which Iceland had a lot of. A large, continuous protected area with many natural wonders, could be promoted as a very remarkable area to visit, more than trying to promote many natural wonders, one at a time. Creating this huge protected area could in fact be very easy to do, and cheap. Much of the area was protected already, and all that was needed to do, to create the largest area of this kind in Western-Europe, was to protect the 79% of the Vatnajokull glacier that wasn‘t already protected. This continuous cluster of around 12 protected areas could then be made into one large, national park.

The scope of public discussion: It didn‘t exist

Generally, one would assume that the political decision of establishing such a huge national park would be based on extensive discussions and wishes among society at large, that had been going on for a long time before being dealt with by the parliament. Historical data shows however, that official and carefully worked out propositions about this came from only one individual. No formal or extensive propositions or wishes had come officially and openly from anyone else, ever.

This one individual who was responsible for all propositions that were presented to society and politicians, in the years before Parliament and government ministers decided to form the national park, was me, the author of this book, Sverrir Sv. Sigurdarson. At the time, I was a student of business administration at the University of Iceland. This project was my own initiative, and I worked alone and unassitsted on it.

The thoughts that started this work were inspired by an economic downturn that Iceland experienced around 1990. I wanted to develop and present a proposition for an option, which the government could do in order to create new opportunities for the country. The work on this started in 1993, the basic propositions were presented in 1995, and my final contribution came out in December of 1998.

My strategies presented and received positive reactions

I received some strategically important reactions for this work. I presented the basic ideas in three, consecutive newspaper articles, and three essays that I sent to a number of influential individuals and institutions, including all members of parliament and ministers. The third paper included the second strategy, of how large hydropower projects could benefit from nature conservation projects.

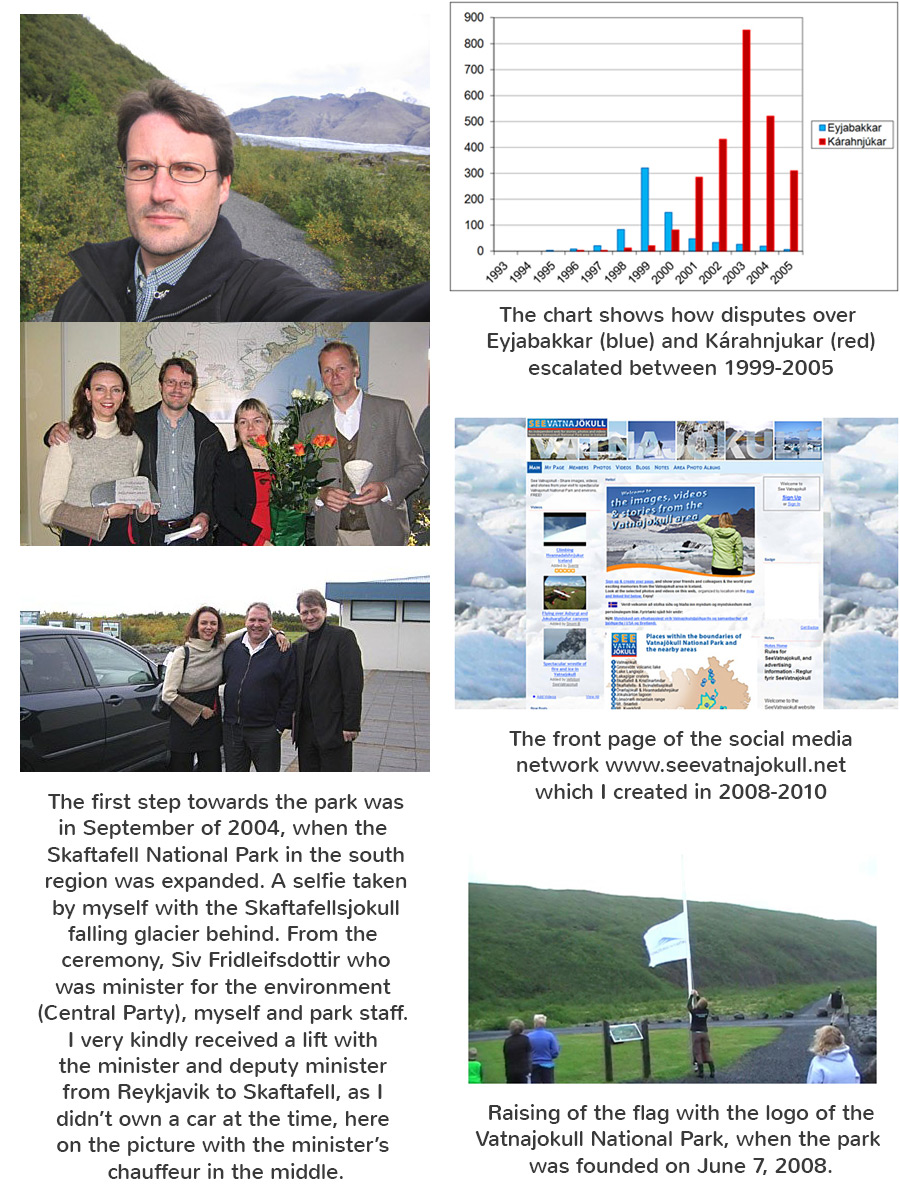

After a tip-off in a letter I received in the fall of 1995, from the managing director of the State planning agency, I submitted my ideas to a prestigious idea competition held by the Ministry for the environment and the State Planning Agency. The results of the competition jury were presented in September of 1996. I received a top prize in the competition. After that, I presented the winning entry in a speech in a symposium that was held, where the minister for the environment, the environmental committee of the Icelandic Parliament, and many other leading figures listened my presentation, and watched the slides presentation.

I was then asked to give an interview in Iceland‘s largest newspaper, Morgunbladid, which appeared on January 28, 1997. The day after came what was perhaps the most remarkable reaction. The newspaper ran an editorial where my ideas received much praise, I was mentioned as the author of the idea, being a university student, and the paper concluded that this idea should be carefully considered when the future of Iceland‘s highland would be decided. I believe that this may have been the only time in the 20th century, where this newspaper ran an editorial about a university student who was presenting some ideas, alone and not connected to any professor or institute at the university, or official student politics. The paper wasn‘t just a newspaper, it was a very influential political institution in itself in Iceland, although it wasn‘t formally a participant in the decision processes and implementation and administration of the parliament, ministries and state.

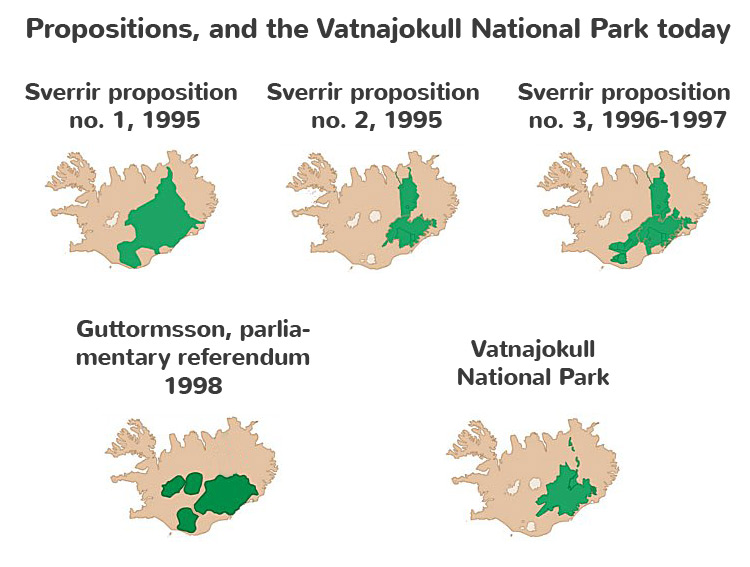

All propositions for this kind of protected area, and the park today.

After this, I spoke at a few other meetings. I received a prize in another competition, an essay competition among university students, held by Visbending, a periodical about economic matters. I also wrote a fourth newspaper article in the fall of 1997, about the proposed planning of the highland. There, I argued that the nature conservation emphasis of the planning was good, and presented data on public opinion in Europe and the US, towards the outdoors and experiencing unspoiled nature. Those I had obtained by purchasing books and reports from abroad.

Finally, I was offered to be among authors in a book with 22 young writers, where the chairman of the publishing committee was the prime minister of Iceland, who was also the leader of the right-wing political party. I had joined the party in 1997. In the book, I wrote about how the Icelandic economy could benefit from an improved nature image of the kind that a large park on Vatnajokull could improve. What was special was, that all the authors in the book had already finished their studies and started their fruitful careers. They would later become government ministers, mayor of Reykjavik, dean of a university, CEOs and be in other prominent positions. The only exception to this was myself, as I was the only one who was still a student when the book was published. The book was published in December 1998, and I graduated with a degree in business administration from the University of Iceland in February 1999. I graduated with first class grades.

Parliament and ministers made their decision

What happened in the same time was quite dramatic. In parliament, a proposition for a parliamentary referendum had been set forth in Feburary of 1998, about four national parks on four glaciers. The proposer was a a left-wing member of parliament, Mr. Guttormsson, and an opponent of the right-wing political party which held the chair of the prime minister. What was interesting, was that neither he nor conventional nature conservationists had ever before presented a proposition for protecting glaciers. The majority in the Parliament wasn‘t interested in forming four national parks on four glaciers. Since 1930, there had only been established three national parks in the country. But for some reason, the majority was interested in having the minister for the environment look into, whether a national park on the Vatnajokull glacier would be feasible. A parliamentary referendum on that was passed on March 10 of 1999. The cabinet of ministers then formally decided that the Vatnajokull national park should be established, in September 2000. What was special was that I didn‘t know about the case in the parliament. I had little connections, and it didn‘t generate a lot of attention. I first read about it in the papers, in September of 2000.

Harsh disputes were rising with bad consequences

There were more things happening as well. When I decided in 1995 to present my ideas about forming a large nature conservation area or national park on Vatnajokull, there hadn‘t been much of disputes between nature conservationists and proponents of hydropower or geothermal power stations, and heavy industry projects. I hoped that I would be able to put this idea into open daylight, without getting into trouble. I wasn‘t planning to do more, but one thing led to another, and I continued adding to this. At the end of it, in the beginning of 1998, such disputes were rising. They were about an area named Eyjabakkar. A year later, plans for Eyjabakkar were laid aside, and instead the hydropower sector was interested in a three times larger hydropower project at Kárahnjúkar. These disputes increased to become the largest dispute in Iceland for many years, as the Kárahnjúkar project and the accompanying aluminum smelter that would use the electricity produced, were to be the largest combined project in Iceland‘s history. It would be worth US$ 3 Billion. The Eyjabakkar and Kárahnjúkar area were both within or right next to the area where the national park would be, depending on where the limits of park would be.

One can be certain, that there were some who supported this gigantic project who were very suspicious of the national park. Usually by many, nature conservation areas and hydropower projects were seen as complete opponents.

A challenging situation

So, around 1999-2000 a very complicated situation had arisen. I was entangled into this situation, it seems, without me having had any interest in being that, and without me having full information about what was going on. In short, this situation included:

- I had finished my involvement in developing and introducing my Vatnajokull ideas, with the publishing of the book in December of 1998.

- Guttormsson had introduced his proposition of a parliamentary referendum for four glacier national parks in February of 1998, which was rejected in February of 1999, and then turned into a proposition of a parliamentary referendum for a national park on Vatnajokull only, also in February of 1999. I had no idea of this.

- I was finishing my studies, graduating, and starting a career, in February of 1999.

- Guttormsson was making a deal with the center-right-wing government of the referendum about Vatnajokull National Park being accepted by the parliament.

- The hydropower and heavy industry sector had started campaigning for a hydropower project in the Eyjabakkar area, close to the park. This was met with great opposition from nature conservationists, many of whom were partners of Mr. Guttormsson, politically speaking. These plans turned into the sector campaigning for an even larger project at Kárahnjukar, which was close to Eyjabakkar, in March of 2000.

- The hydropower and heavy industry sector, traditionally influential in the right-wing political party, was thus probably quite skeptical about a huge national park on Vatnajokull, which was in the same area as the Eyjabakkar and Kárahnjukar. But a part of the right-wing party was making a deal with Mr. Guttormsson about forming the park.

- It was easy to trace who had been talking about forming a park on Vatnajokull glacier, even if it was the left-wing Guttormsson who had pioneered the case in parliament.

- I wasn‘t able to talk to anyone as I had no idea about what was happening in parliament. I first learned of the Vatnajokull National Park after it had had been decided, in September of 2000. At the time, my situation was already very challenging, and the factors that could change that to the better weren‘t available.

- I had never spoken in any meaningful way to the left-wing member of parliament, Mr. Guttormsson at the time, but perhaps someone thought there was a connection since he was proposing what was very close to what I had talked about, which was perhaps not a serious thing but didn‘t win me any points, wasn‘t a reason to give me any support, with certain individuals in the right-wing people.

- It should be very clear, that this kind of a situation isn‘t normal at all for a young man, who is simply a university student, and not politically active, or connected, at all.

What happened for me, was that instead of building a fruitful career, I faced a very challenging situation when it came to getting, and keeping, a proper job. I am sure that the fierce, many years long disputes between nature conservationists and the hydropower sector, and the plans for the national park right in the area, created a very poisonous environment for me. I was just a newly graduated, unconnected and inexperienced person with a business degree. Business life generally wasn‘t positive towards nature conservation at the time. I didn‘t receive any threats or hostilities, but the career reputation of a person with a business degree is more fragile than many think, and it can be easy to influence it in a negative way.

I had been the only one with a valuable idea

It was half a decade later that I finally learned about my fundamental role in the arguments for the formation of the Vatnajokull national park. Then I learned that in Iceland‘s history, only one person had presented focused ideas and arguments for protecting the whole of the Vatnajokull glacier and surrounding areas into one protected nature area, before the matter was discussed in parliament. Conventional nature conservationists had never done that. This meant, that there was only one man who had brought to the attention of the center-right political majority of politicians, that it was possible to do something like this on the glacier, with attractive arguments for doing it.

At the time when I learned this, there had also been presented evaluations of how the national park could possibly increase foreign exchange revenues from international tourists, who would be drawn to Iceland because of the national park. The numbers were very high. In today‘s prices, the turnover in the economy could increase by as much as US$ 300-800 million per year. It should be noted that the Icelandic nation, and economy, is roughly around 1/1000 of that of the United States, so similar numbers in the US as percentage of GDP (gross domestic production) would be around 1000 times higher. A small food for thought. This revenue increase could increase government tax revenues so, that they would be sufficient to pay the running costs of all universities in Iceland, and even more than that. It seemed clear that the side project I had worked on when I was a university student could possibly pay itself off very handsomely for the Icelandic nation.

I tried to introduce my role in laying the theoretical foundation for the national park, and to point out how valuable it could be. That I did in 2004 and 2005. But unfortunately, the disputes over the huge hydropower project had reached its absolute top the year earlier, and were still very much active. Those who talked about nature conservation weren‘t popular at all in the business world. The national park itself wasn‘t formed until four years later, in 2008, after the hydropower plant and aluminum smelter had been built, and the disputes had obviously died out.

My challenges regarding career and financial income weren‘t resolved. After a certain time, this kind of situation is feeding on itself. Even if nobody is against you, as the disputes have long died out, then the long time where one has been in a challenging situation becomes an influential factor in itself. In 2008, the entire banking system of Iceland collapsed, and a deep recession set in.

The video

In 2009, I created a video about the economic potential of the national park, which has comparison with estimated economic impact of national parks in the USA and UK (and many nice photos). I created an English version, which can be seen here: https://youtu.be/npV3J3L621g

Misunderstanding regarding the true origins

When I introduced the ideas for forming a large, protected area on the Vatnajokull glacier, I was the first in history to do that. Those who reacted positively were mainly open-minded individuals who were connected to the right-wing political party, the Independence Party. However, historically, supporters of the right-wing party were not interested in nature conservation or new protected areas. They were pro business, pro industry, pro hydropower projects. Thus, I sense that the idea was sort of an orphan within that party.

In parliament, it was the ultra-left-wing Mr. Guttormsson who presented his novel idea of focusing on forming four national parks on four glaciers at the same time. This was rejected, but out of it came the solution of forming the national park on Vatnajokull glacier. That solution, the right-wing Independence, and the central Progressive Party (Framsoknarflokkur) were interested in giving their support to. Because of this, the general understanding became that is was wholly a project initiated by Mr. Guttormsson. His supporters on the left wing of politics have been very comfortable holding up the story, that the Vatnajokull National Park is his idea, and his idea only.

Myself, the actual thinker behind the proposition and strategic arguments for Vatnajokull, haven‘t been remembered for this. Of course, when I was introducing my ideas years ago, I actually tried to generate as little interest around myself as possible. I never talked about my ideas at school, and I didn‘t spend much time connecting with people to have a discussion. I was too busy working on my university studies. So there is a reason why not many have been remembering my part. But that doesn‘t change the fact that I am the one who formed the strategic ideas that opened the eyes of those who were in charge in politics. Those were parties that had never been very keen on forming large nature conservation areas. There are people who know the truth about the origins of this large idea, but they are not many. It‘s a long time that has passed since this was.

The full story was not easily visible

The challenges that I endured regarding building a normal career started very early. In a perfect world, you would be surrendered by people who have perfect access to correct information immediately, and who see thing in a balanced and just manner, and are ready to support a good cause and support someone who wrongfully is in trouble. In reality, unfortunately the sitation wasn‘t so. People saw that my career wasn‘t developing like it should be. Usually, when someone is facing such a development in his career, that is because that individual has done something horribly wrong, has violated some important rules, or the person is suffering from some personal problems that are causing the challenges.

This was not the case with me. I had been doing good and just things, in fact things that are close to unique. I hadn‘t done anything wrong, and I wasn‘t suffering from any personal problems. The bad thing was that the good things I did seem to have collided with some of the most massive disputes and struggles of economic interests in latter times, where hugely powerful special interests were ready to pull strings in many ways, openly or behind the scenes. And it wasn‘t openly obvious.

Correct information about what was going on at the time wasn‘t available to me until it was too late to even try to do anything. And when information seemed to be becoming clear, then I couldn‘t trust that people around me, friends, acquaintants and family, would have access to the information, or would be interested, or would have full understanding and acceptance of the complex political and economic interest situation that had been built up, and was unmatched in latter times. People don‘t feel sorry for, and don‘t want to support, someone in this situation, when they don‘t know the details. So the fact was, that instead of having people‘s full understanding and support, I was viewed very sceptically, and some people were closer to turning their back on me rather than showing support. The situation was complex. People didn‘t all react in the same way in the same moment.

Not often seen in Iceland

As time progressed, I also realized a few things about Icelanders. I couldn‘t be sure, that Icelanders would be able to fully understand and support the situation. Icelanders are known to be early adopters of new technologies, new fashion, and so on. But it is a fact, fact that most of these technologies and innovations are researched, developed, tested and first marketed abroad, among the large, developed nations. This means that people don‘t have much experience, and thus not much knowledge, about the development process itself, which often requires much work and care.

The work on researching and developing the idea for Vatnajokull glacier was conducted in Iceland, by myself, but I soon realized that Icelanders didn‘t have a good understanding of what it meant. Plus, information about that process weren‘t formally accepted, even if I was trying to present them to further my case. Perhaps they didn‘t realize, that such a huge project could actually be the fruit of work dome by an unknown university student. Also, many are not well into marketing-thinking. Thus, I learned that they didn‘t really believe in my accomplishment.

The situation is made more complicated by two things. First, it is for the fact, that among the right-wing in politics there was historically a great dislike for nature conservation. Nature conservation was seen as the enemy of business and the industries. There were even voices talking negatively about nature itself and the highland. Historically, nature had been seen as an enemy by many through the centuries, a dangerous force in the lives of Icelanders, and these negative attitudes were still lurking beneath the surface of the Icelandic psyche. Even if tourism has boomed spectacularly in recent years, increasing 8 fold since I was introducing my ideas, and tourism is now the main generator of foreign exchange revenues for the nation, then these negative emotions haven‘t given way officially, being fully replaced by positive attitutes towards the nature and its protection by everyone, officially and openly. But I feel that the atmosphere is shifting, and believe it will in the next five years.

The second thing that made things more complicated is the individuals who made my situation challenging, as they were among the most influential and connected in Icelandic society. To get ahead in society, to get and keep a good job and build a career, seems to have been very challenging for a young, recently graduated person with a business degree.

So these three things, the inexperience and lack of understanding among the older generations regarding research and development, the negative attitude towards nature, and the people who probably disliked the Vatnajokull ideas, and thus perhaps disliked my contribution and possible future contributions (although actually I wasn‘t planning any further contributions), made the situation very challenging. On top of this, there are more sides to this issue that explain why things developed as they did, but I will not talk more about that here. But it was difficult to experience, that people didn‘t understand that it was beneficiary that someone would spend time developing a new solution that could help the creation of jobs. They simply didn‘t care.

One thing might however explain a bit better what was unusual in this. In the years before and during my university years, I was developing and introducing strategic ideas on protecting a glacier, to form a large protected area in order to improve Iceland‘s possibilities in marketing the tourism industry and create new jobs. Was this something that was very common among young people, like playing football, watching TV and going to parties is? Actually, no. Doing this, with this kind of thinking, wasn‘t common at all. Was I then in some way different from the most common type of Icelanders? Yes, actually that is the case. Not necessarily better or worse, just different and that is the reason why I was doing things that weren‘t commonly done.

A big part of my ancestry is traced back to Danish/Swedish upper middle-class, as my family was one of the most influential ones in Iceland when Iceland was part of the Danish kingdom (Iceland became an independent republic in 1944). Before that, my ancestry probably stretches south to Prussia, now part of Germany. My grand-grandfather provided services to the king of Denmark, Christian X, who was also the king of Iceland, during the very few visits of the king to Iceland back then. The point is that people in Denmark, Sweden and Prussia would think, work and organize things differently than ordinary people in Iceland at the time. Iceland was traditionally the poorest and least developed country in Europe, consisting of simple farms and fishermen in Europe‘s harshest living conditions. These roots in the past do still have some influence today, although society has also changed much. Icelanders are very bright and capable in many ways, they are very agile, resourceful and masters of tactics. But in my opinion, they are not good at seeing the big picture and present organized results, they are not good at disciplined discussion, and they are not very strategic. The people of Sweden and Prussia are much more in that department.

The idea about protecting the Vatnajokull glacier was, at first sight, a ridiculous idea, and nature conservationists had never suggested anything of the kind. But the argument was researched and thought out to the extreme, it was very strategic and economical, and there were some very influential and broad minded individuals who saw, that this would be a good idea. So it was passed as a political decision by the parliament and cabinet of ministers in a very short time, although actually this was something that only one person had ever talked about, an unknown university student. I understand the ordinary Icelander very well, as I grew up in Iceland, but this part of my background, and this kind of thinking and how it is different from the normal Icelandic way of approaching life, they don‘t understand it. When normal Icelanders are confronted by my way of thinking, many don‘t understand. It is the truth that sometimes when people don‘t quite understand things, they find it weird, or even react negatively. For me, to start developing a strategic proposition was a natural and logical thing, but many weren‘t „on the same boat“ so to speak. Trying to discuss this with people in Iceland, I repeatedly experience lack of understanding. They don‘t seem to get it, what is the difference between this, and the usual innovations that come to Iceland automatically, without anyone in Iceland having had anything to do with it. In case if you were wondering what kind of guy does something like this, with these results, then here is the answer. But maybe this kind of activity, and these kinds of results, are rare in any society?

When one looks at Iceland, it is easy to see that the country is very prosperous. But the reason why it is prosperous is probably different from what many think. When you analyze Iceland‘s history in the last 80 years, you see that the prosperity can be attributed to unusually favorable situations that came up. These situation were not created by Icelanders themselves. Thus one starts to understand what is the real history of Icelanders, what are their strenghts, and what are they not.

It should be obvious, that it would have been better for me not to develop and introduce the Vatnajokull ideas. But I did, and now I must find a way out of that maze. If I hadn‘t introduced my ideas, then there would be no Vatnajokull National Park today. The situation would have remained mostly unchanged, because someone must point out an option in the beginning and present good argument for it, which at least some of those in the ruling political parties find interesting. Nobody was likely to do that, not in this location on a glacier, and not in such a way that the right-wing in politics would be interested. This is something which many don‘t understand or don‘t want to acknowledge. The park is there today, the largest in Western Europe, a medium size government institution with up to 100 employees in the summertime, founded by the government after the decision of politicians. There are many who will be unable to fathom that this huge phenomena wouldn‘t exist if it hadn‘t popped out of the head of a completely unknown university student in the beginning, more than two decades ago.

As time passed, It wasn‘t that people were actively working against me. They simply weren‘t doing anything, neither to improve my situation or to make it worse. Things remained unchanged, and it has to be said that time passes very quickly.

Stepping forward and telling the whole story could be very risky. I could not be sure that people would understand or if they would find the story interesting and trustworthy. Those who had taken part in the disputes, which I did not take an active part in, were among the most powerful and best connected in society. To step forward and tell the story could be risky, when only a short time had passed since the end of the disputes (and disputes are still going on, this time in other areas). Thus, I had to simply endure and try to find a peaceful way out of these challenges, while the disputes between nature conservationists and pro-energy and industry continued, and the government was building the national park without my participation.

The front page of the book Skrefin ad Vatnajokulsthjodgardi.

Where is the proof?

This text has described situations and events that are in many ways out of the ordinary. They are especially out of the ordinary for a humble university student, who simply has before him the general task of commencing his studies to finish a degree and start a career. Where is the proof for what has been described here?

The main set of proof is in the book Skrefin ad Vatnajökulsthjódgardi, or „The Steps Towards The Vatnajokull National Park“ which is 282 pages long in A4 format, with more than 100 color images. This book is supposed to contain, as far as I was able to collect, all contributions to the discussions, and a description of all that happened before the Icelandic Parliament started discussing the possibility of national parks on glaciers. These are events and discussions that took place from 1992 to 1999. The main focus, of course, is to pinpoint which propositions, which contributions, and which discussions influenced the politicians to make this decision, as the parliament was presided by the central and right-wing political parties.

It can be said that around 80-90% of all that was contributed regarding the possibility of forming this kind of area on Vatnajokull specifically, was contributed by me.

The book, which is in Icelandic, can be found in libraries in Iceland. It can also be downloaded for free in PDF format on the web page www.seevatnajokull.com/bok.

Explaining this is probably necessary

I am not ready to accept what most people will conclude automatically, that the challenges I encountered were simply my fault (as such challenges would very often be). That is not the case here. Therefore, explaining this entire story is necessary, so that I may have a better chance of doing something positive with the four opportunities that are described in part one of this book. The truth is, that what happened around the Vatnajokull issue was not a blunder by me, but a rather unique story that deserves to be known.

Comments about my work on the Vatnajokull strategy:

A statement by Ms. Siv Fridleifsdottir,

Icelandic Minister for the Environment 1999-2004.

A comment by Ms. Siv Fridleifsdottir

former Icelandic Minister for the Environment, from 2014

A statement by Mr. Stefan Thors,

Director of the Icelandic State Planning Agency.

A statement by Mr. Hugi Olafsson,

department head at the Icelandic Ministry for the Environment.

A statement by Mr. Tómas Örn Kristinsson,

Editor of Visbending, Icelandic magazine about economic matters.

A statement by Mr. Kári Kristjánsson,

board member of the Icelandic Nature Conservation Council.

Entrepreneurial projects

The ideas for Vatnajokull aren‘t the only ideas I have generated. For instance, the original idea for audio hi-fi equipment is in fact an older idea than the Vatnajokull glacier ideas. And the audio hi-fi idea still holds promise. My focus has been on trying to create my own opportunities.

What happened to the propositions, arguments and strategies about Vatnajokull that I developed, is a world-class accomplishment for sure. Not many have matched this in the 20th century.

But I believe that my other ideas have potential that is not of a lesser scale, although they will never become as big in terms of geographic area.

What I am most interested in is to continue, and create success and wealth through implementing some or all of the opportunities that are described in Part One of the book.

Let‘s make that the goal.

Sverrir Sv. Sigurdarson

Email sverrir@sverrir.info , main website www.sverrir.info, project service www.marktak.is.

My Vatnajokull social network: www.seevatnajokull.net, my ideas page: www.ideabun.com

Phone: +354 864 0023. Skype: sverrirsveinn

Image credits for the images from the Vatnajokull National Park on page 21: People are tiny near the giant Dettifoss – ciamabue – CC Attributon, The Jokulsa a Fjollum river snaking through Jokulsargljufur – Stig Nygaard – CC Attribution, The pond at the bottom of Asbyrgi – by r h – CC Attribution, Mt Herdubreid above the lava field by ezioman – CC Attribution, Standing above Lane Askja by ndanger – CC Attribution sharealike, In Kverkfjoll 7 the ice cave by ezioman – CC Attribution, Snfellogfleira084-atlilyds-photobucket, Ice formations in Jokulsarlon lagoon by sly06 – CC attribution, Parts of Vatnajokull south side by travelwayoflife – CC attribution sharealike, On Svinafellsjokull by Giåm – CC attribution, Svinafellsjokull by Giåm – CC attribution, Craters of Lakagígar by 47Mhg491Vgb – CC attribution sharealike